National Museum Zurich

| 20.3.2020 - 16.8.2020

The Middle Ages were a rough time. Especially for women and their prospects. Life in a convent was a welcome way out, affording not only greater freedom, but also education, influence and sometimes power.

Medieval nuns – this usually conjures up an image of a group of women living an ascetic life, interested only in a world of seclusion inside the walls of their own convent. But there was another reality that was more diverse, surprising and worldly than people might think.

The first nunneries were founded in Europe from the 5th century onwards. Convents offered women opportunities they would have been unlikely to have otherwise: access to higher education, social welfare provision and the chance to break away from the close strictures of their families. Not infrequently, this decision was also associated with advancement within the monastic community. The highest office was that of abbess, prioress or mistress. Managing a nunnery was challenging, requiring diplomatic skills and a high level of education. Religious centres often had close ties to politics and business, and had a hand in shaping secular affairs.

Examples of this include Catherine of Siena (1347 – 1380), who successfully evaded her own marriage, entered a lay order, became a source of inspiration for a growing following, and was ultimately an important voice in discussing matters of church policy with popes. Or Pétronille de Chemillé (1080/90 – 1149), abbess of the double monastery of Fontevrault. She won recognition in a male-dominated world – against massive political resistance, she succeeded in consolidating the young, up-and-coming order. Under Pétronille’s leadership, Fontevrault gained political and economic influence and became a strategically important place for the powerful of France. The order included both women and men, all of whom were under the abbess’s authority. Also worthy of note is the commanding position of the abbess (Fürstäbtiss) of the Fraumünster abbey in Zurich. In the 13th century she was the chief office-holder (Stadtherrin) of the city, appointed burgomasters and judges, and had voting rights and the right to sit in the Imperial Diet of the assembly of Princes of the Holy Roman Empire (Reichstag der Fürstenversammlung des Heiligen Römischen Reichs).

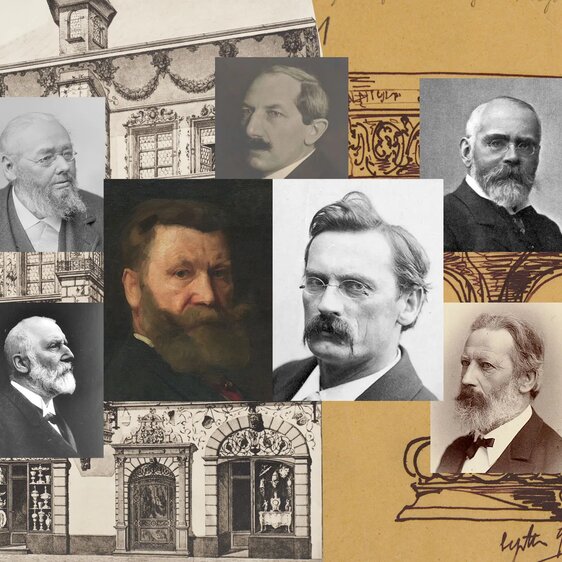

With the help of 15 representatives of this august group and precious exhibits from, among others, the Vatican Library and the Germanisches Nationalmuseum, the exhibition looks at the diverse ways of life of ecclesiastical women in the Middle Ages, and reveals what opportunities were open to them. The exhibition explores the important position of the convents in educational matters and their links to politics and the economic system, as well as the still often underestimated formative influence these women had on theology. Rounding out the exhibition is an installation by Annelies Štrba. Video artist Jürg Egli has amalgamated her photographs of church windows, Madonna figures and magnificent gardens to create a new work which puts women and the female at the centre.